My Quest For 65 Dior Dresses

As well as a review of the best book I've read so far this year.

Hi everybody. Today's post was supposed to be a special edition magazine about the solo writing retreat I’m meant to be on right now. But my husband gave me Covid—even though I told him I prefer gifts of diamonds! It's my first time, and I’ve been very lucky; besides a mild fever for about 24 hours and a slightly blocked nose, I've had very few symptoms and began to feel normal again after only a couple of days, besides the tiredness and slight decrease (hopefully temporary!) in mental acuity.

It means that I didn't go on my writing retreat, which is a shame because I've really been hoping for a few days to absorb myself in the world of my book properly. And it means that my focus for writing a regular magazine isn’t quite what it needs to be.

Luckily I’ve been writing posts and articles for years and have a glorious abundance of pieces you might have missed when they were first published and that I think are worth sharing. So I’ve pulled one of those out of the archive (the original was first published in Sunday Life), dusted it off and refreshed and expanded it substantially for you.

But First!

I have to share this book recommendation with you. Claire Kilroy’s Soldier Sailor is the best book I’ve read so far this year. It’s about that terrifying, tender, apocalyptic and occasionally beautiful time when your first child is a baby and you feel like you’ve lost yourself. It’s about how much labour is involved in those first months (years?) when you quit your job to stay home with the baby and something as seemingly simple and small as cooking dinner can make you feel like you’re losing your mind:

I cried over the onions and chopped the carrots. I cannot be the first woman to wonder how many vegetables I have peeled. That figure should be displayed on our gravestones: This woman peeled however many tonnes of potatoes, let’s hear it for Mrs Whatever! And her husband? Well, he just ate them.

Yes, it is achingly funny too. I laughed aloud at the above quote. God, this book put me right back there, with the baby who wasn’t even on the percentile charts because she just wouldn’t eat, the baby who looked like a starveling beside all the other gorgeously chubby babies at mothers’ group; back there with the tears and the destroyed dinners and the husband who just came home and ate the f#$@!g potatoes.

I think I’m reading the book at the right time though; my kids are now 14, 16 and 18 and my husband and I have had many, many arguments about sharing workloads and the fact that there are two parents in the house rather than one and that both of our careers are equally as important, and I can now look back on those years with the eye of a survivor. With a husband who now probably cooks more dinners than I do. So approach the book gently if you don’t quite have that distance from the events yet as it could just as easily make you cry as laugh.

Here’s another quote that has that same delicate, perfect balance of cry/laughter. The narrator’s husband is sitting in the recliner chair watching Blade Runner after having just come home from work and after the narrator (the titular Soldier; her baby is the Sailor) has endured a day of baby hell:

And you know men, men, men nod solemnly at that Blade Runner speech—tears in rain and fires on Orion—and they feel themselves part of a noble endeavour, believe they’ve experienced something epic right there with a beer on the couch. Here’s my ennobling truth, Sailor: women risk death to give life to their babies. They endure excruciating pain, their inner parts torn, then they pick themselves up no matter what state they are in, no mater how much blood they’ve lost, and they tend to their infants. Your fires on Orion and your Luke, I am your Father. Tell me, men: when were you last split open from the inside?

I have never seen Blade Runner and I have no idea who Luke and Orion are, but I don’t need to; Kilroy writes it so you just know exactly. So that a laugh bursts out. And so that you remember, and weep a little too.

Back To Dior …

Yes, slightly awkward segue, but this newsletter is always about all the different facets of my life: awkward and opposing things often rub up against one another. The original essay that I’ve refreshed and expanded here for you is one I wrote in 2020 when my book The Paris Secret was published. Amongst many other things, my novel is about a woman finding a collection of sixty-five haute couture House of Dior gowns in an abandoned cottage belonging to her grandmother—one gown for every year since the very first collection in 1947. And yes, you’re right if you think I was writing about a dream I wish might come true for me one day!

Alas, I’m still waiting to stumble upon my haute couture inheritance. So I had to turn to museum collections and exhibitions to make my selection of sixty-five gowns to put in my fictional wardrobe. Luckily for me, the year I was researching that book turned out to be the Year of Dior, as far as museum exhibitions went.

So this article has no solid writing tips in it (except always work a little ahead of your deadlines as you never know when illness or children or life is going to cause you to have to do no writing at all for a week or two), so my apologies if you only visit Bijoux for the writing tips. But I know lots of you are readers, Francophiles and fashionistas, so I hope you’ll get a lot out of it. And it’s also a glimpse at exactly what a writer does when they say they’re researching and some of the research I got to do for this book was actually very special—how often in life do you get to go into the archives of a museum and put your (gloved, of course!) hands on a 1947 Dior gown? In fact, I’ve often found the research, especially this kind of research, to be at least as fun as the actual writing of the book, if not more so!

My Quest Begins: From Melbourne to Paris

I could have relied on photographs in books about Dior to create my wardrobe of sixty-five gowns for The Paris Secret. But, in his autobiography, Christian Dior says that the most important thing about a dress is that it should be ‘expressive’. There’s no better way to discover exactly what is being expressed in an arrangement of silk and thread and pleats and buttons than to see it for yourself.

About two years prior to this research adventure, I’d been wowed by Dior’s Venus and Juno gowns at the Met Museum’s stunning Manus x Machina exhibition, so I knew Dior was right. Those gowns made such an impression on me—how could they not?!—that they were on my list right from the outset. But the rest, I had to search for. (All the photos in this post were taken by me, at the museums mentioned).

I began my quest at The House of Dior: Seventy Years of Haute Couture exhibition at the NGV in Melbourne. I didn’t want to choose the most famous pieces: the chartreuse chinoiserie gown that Nicole Kidman wore to the Oscars ceremony in 1997 is, for example, too well-known and too indelibly linked to the actress. Conversely, I don’t think you can write a book about Dior and not feature his most iconic piece of all: the 1947 Bar Suit, which didn’t disappoint when I finally saw it.

I think this piece is all the more poignant when you understand how badly French women had been starved for all the years of war, and that rations were still in place in Paris in February 1847 when Dior showed the Bar Suit. You see the waist of this suit in a whole new light when you know this.

I particularly loved the red dresses at this exhibition, including ex-Dior Creative Director Raf Simons’ sublime Look 21 in heart-stopping crimson, and one of Dior’s very first gowns, the Aladin, in a subtle but delectable garnet. Both of these dresses expressed just what I wanted: courage, style and knock-out glamour. They became the opening numbers on my list of sixty-five dresses.

From Melbourne, I went to Paris to see the exhibition Dior: Couturier du Rêve at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs. And in Paris, it was the dresses that seemed to be having the very best time that I loved the most, like the fabulous pink Opera-Bouffe, which sassily adorns one’s derrière with a gigantic silk faille flower. Onto the list it went. I have no idea how you would sit down in it, but I guess it was made for dancing rather than sitting!

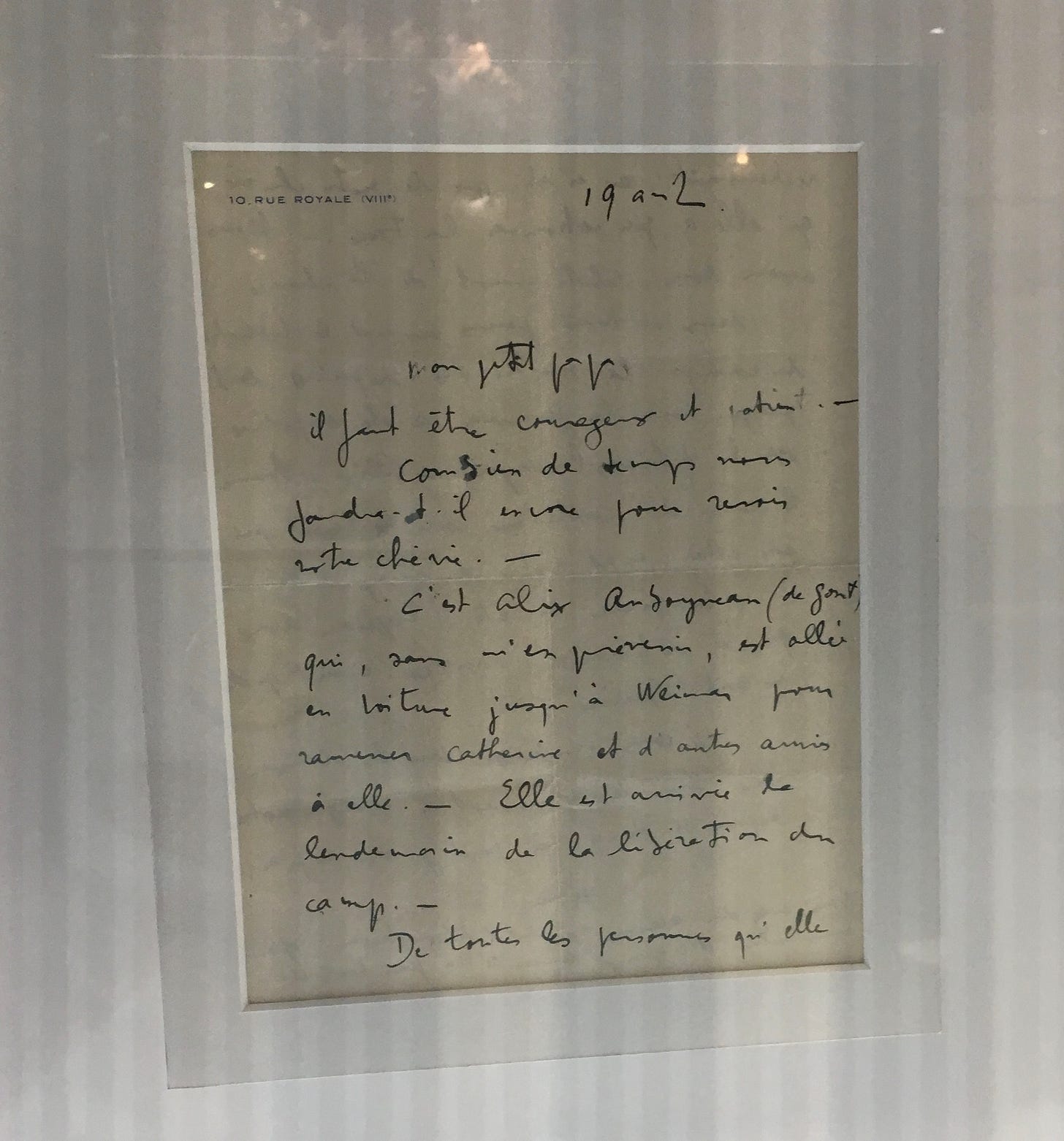

On a more sober note, amidst the silk, I found something else that tied into my book: a letter from Christian Dior to his father to let him know that he’d finally had news about his sister, Catherine Dior. Catherine worked for the French Resistance, was captured by the Gestapo and sent on le dernier convoi, the last train out of Paris, the train onto which the Nazis tried to hide the evidence of their crimes by emptying the Paris prisons of resistance fighters. Catherine was sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, a concentration camp for women. She survived, just, and in this letter dated April 1945, Christian Dior describes his joy at the news that she is returning to Paris alive.

From Granville To Sydney

The Dior family used to live in Villa Les Rhumbs in Granville, Normandy. It’s now a museum dedicated to Christian Dior and it was my next stop after Paris. The house itself is a delicious pink bon-bon, sitting atop a cliff, surrounded by flowers and the sea. Perhaps it seems obvious that, in a house by the sea, it would be a blue dress that caught my eye. But the Soirée d’Asie from 1955, a slinky, skin-tight sheath of teal blue satin was one I’d never heard of and it caught me by surprise, most definitely expressing its wish to be included in my fictional wardrobe for The Paris Secret.

My last stop was back in Australia at the Powerhouse museum. I wanted to touch a Dior gown from the late 1940s, to look inside it and really examine it. How could I know what it was expressing if I’d only looked at it from the outside?

So I sent an email to the Powerhouse Museum asking for help. As luck would have it, at the exact same time, one of the fashion conservators at the museum was reading one of my previous books, The Paris Seamstress. So she knew who I was and was more than happy to help.

I donned a pair of rubber gloves and descended with her into the depths of the museum. Slowly, she pulled open a large drawer. Nestled inside, in acid free paper, was the Christian Dior Moulin à Vent, or Windmill dress, from 1949.

The interior of the dress was a marvel. I had no idea how many hook and eye closures were used by couturiers like Dior to make certain that a dress shaped itself properly around a body, nor that covered lead weights were sewn into each piece so it would hang correctly. It was just as interesting to see the internal construction of the dress as it was to gape at its stunning exterior, to touch what few others ever get to see.

My phone is now weighed down with an excess of the picturesque – all the photographs I took of the gowns so I could refer to them while compiling my list. Was it hard to narrow the list down to sixty-five dresses? Mais oui! Perhaps I’ll just have to write another book featuring all the dresses that didn’t make it into this one!

It was just mesmerizing just reading your words about the beautiful Dior gowns. Thank you so much for sharing Natasha.

It must have been to die for to actually feel a Dior gown plus the inside it as well! How captivating. Keep writing Natasha maybe the second book would be great the gowns that didn't make it to the 65 list.

Thank you very much, once again Natasha. Your writing is so descriptive and beautifully created that I love immersing myself into your space- for just a little while.