It would have been Catherine (Ginette) Dior’s 107th birthday last month and, by sheer coincidence, I also had the opportunity last month to talk about Catherine to a group of people participating in Dressed: The School of Fashion, an offshoot of my favourite fashion podcast. So I thought why not take a look at her extraordinary life in more detail here.

My regular readers will remember Catherine Dior as a character in my novel, The Paris Secret. But who was she really, and why do so few people know about her incredible courage—beyond the rather anaemic and often fanciful portrait of her in the Apple TV series, The New Look?

I first read about Catherine Dior in 2016 Anne Sebba’s wonderful book Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died in the 1940s, which I can thoroughly recommend to anyone interested in the stories of women who've been left out of the standardised version of history. My interest was immediately piqued when I came across the brief mention in Sebba’s book—how was it that I knew so much about the famous couturier, Christian Dior, and so little about his younger sister, Catherine?

At that point, I knew her only as the inspiration behind the house’s foundation fragrance, Miss Dior, and had no idea that Catherine worked for the French resistance during WWII, that she was captured by the Nazis in 1944 and sent on le dernier convoi—the last prisoner train out of Paris before it was liberated by the Allies—to the horrific Ravensbrück Concentration Camp.

Miss Dior: So Much More Than a Fragrance

The anecdote about Catherine that’s the easiest to find on the internet and is more well known than her bravery goes like this:

It’s 1947. Christian Dior has created a perfume and he doesn’t know what to call it. He’s discussing various options with his team and suddenly Catherine walks into the room. Mizza Bricard, one of Dior’s right hand women (who I wrote about here), says, ‘Look, here's Miss Dior.’

And Christian says, ‘Miss Dior. That's my perfume.’

He knew he wanted to honor his sister because of all that she’d done during the war, and so this perfume, which many, many people still buy today, is one of the ways in which Catherine Dior is remembered in the world.

But there's a lot more to Catherine than just a beautiful bottle of pink perfume.

The Injustice of Who and What the World Remembers

Catherine Dior survived nine months of imprisonment in Ravensbrück—Hitler’s horrific concentration camp for women—and various other Nazi sub-camps. And she survived a death march in April 1945 as the Nazis moved their prisoners deeper into Germany to try to hide their crimes from the advancing Allied armies.

She emerged from the camp at the end of the war barely alive, suffering from dysentery and pneumonia, riddled with lice and virtually a skeleton. She couldn’t eat properly for weeks because her stomach had shrunk so much as a result of being starved almost to death.

But Catherine's work with the resistance was so courageous and so important that, after the war, she was awarded a Croix de Guerre and the Légion d'honneur by the French, and the King's Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom by the British. Upon discovering what she’d done, how she’d suffered and how extensively awarded she was, the terrible injustice of what and who the world remembers struck me immediately—most people, when asked to name a famous couturier, would probably be able to come up with the name Christian Dior. But his sister Catherine—a woman who fought for freedom for her country and who almost lost her life in that struggle—has been forgotten.

Surely she’s the true heroine of the Dior siblings?

I believed she was, so I embarked on a quest to find out more about her and to try to write about her in my novel, The Paris Secret, as authentically as possible. My quest for answers took me across the globe, from Melbourne to Paris and finally onto the Dior family home in Normandy.

The Start of My Quest

In Christian Dior's autobiography, Dior by Dior, he mentions Catherine perhaps just four or five times. He confirms that Catherine worked for F2, the British supported Resistance organisation that primarily worked out of southern France and that, once or twice, Catherine used her brother’s Paris apartment as a meeting point. The scant number of references isn’t because Christian didn't love his sister; it was because Catherine was very reticent about what happened during the war—like so many French women who worked for the Resistance—and she spoke very little about it after she returned from Germany. I suspect Christian was both respecting her privacy and was also devastated by what happened to his sister—he rarely spoke about it either.

Also on the historical record was the information that Catherine was drawn into Resistance work after meeting Hervé des Charbonneries in the late 1930s. She was living at a property in the south of France, a property where Christian sometimes stayed, and she fell deeply in love with Hervé at that time, and joined the Resistance network he was working for.

Given the recorded information was so scant, I knew I was going to have to look beyond the books. Luckily for me, the year I was researching turned out to be the Year of Dior as far as museum exhibitions went. And one of those exhibitions was actually happening at the NGV in Melbourne Australia, which is only a quick 3 or 4 hour plane trip from my home in Perth.

There were lots of beautiful Dior dresses at that exhibition; I’ve shown my photos of some of those dresses and written about them in the post just below, but I didn't find out a single thing about Catherine at the exhibition.

My Quest For 65 Dior Dresses

Hi everybody. Today's post was supposed to be a special edition magazine about the solo writing retreat I’m meant to be on right now. But my husband gave me Covid—even though I told him I prefer gifts of diamonds! It's my first time, and I’ve been very lucky; besides a mild fever for about 24 hours and a slightly blocked nose, I've had very few symptoms…

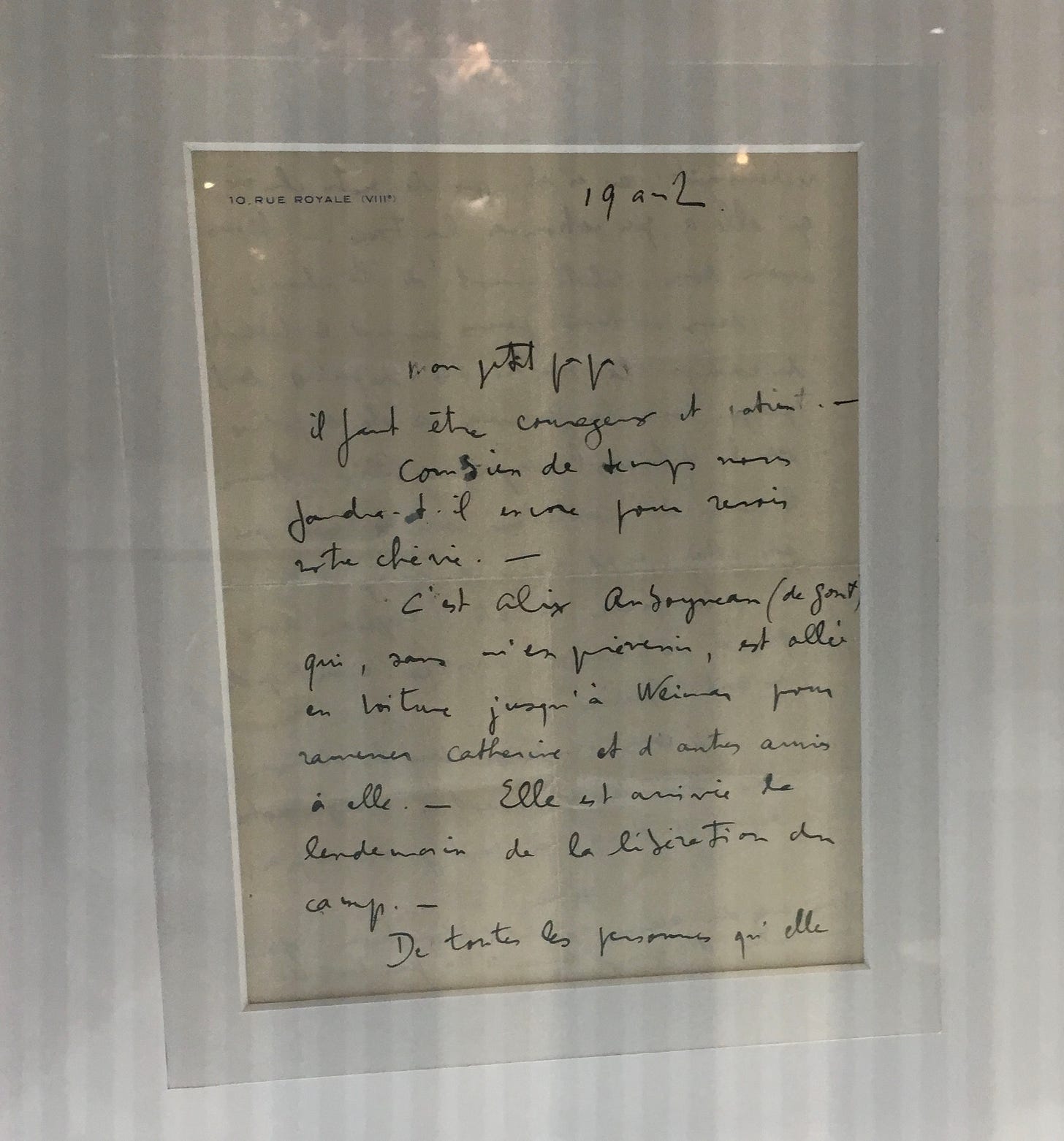

Undeterred, I headed overseas, this time to Paris and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs for another wonderful Dior exhibition: Couturier du rêve (Couturier of Dreams). Once again, there was a fabulous display of Dior gowns, but almost nothing about the heroic Catherine, apart from one tiny letter amidst the glamour, pictured below.

It’s a letter from Christian to his father confirming that Catherine had managed to escape from Ravensbrück in April 1945 and was on her way back to Paris. Christian is effusively delighted—he’d written many, many letters to the Red Cross and to all of his contacts for months after Catherine disappeared, desperately seeking to find out what had happened to her.

So here was one piece of concrete evidence about Catherine. But there was still a huge gap:

What had happened to Catherine in the years preceding April 1945?

What had happened to Catherine while she was working with the Resistance?

What had happened to Catherine at the concentration camps?

And what had happened to her in that critical period after she had escaped from the camp and returned to France?

Going Back to Catherine’s Childhood

What I found at the museum actually raised a lot more questions, instead of giving me any concrete answers. Seeking those answers, I went to Granville in Normandy, France, where the Villa les Rhumbs is located.

The villa is the ex-Dior family home—a beautiful pink house, perched on a cliff and surrounded by flower gardens. It’s now a museum dedicated to the Diors—to Christian more specifically—and it’s well worth a visit if you’re ever in that part of France.

The museum did have several photographs of Catherine, both as a child and a young woman, and it provided some information about her life at the villa as a child. She and Christian were very close, despite the twelve year age gap. I saw her old bedroom and was able to walk through all the rooms where she had spent time every day of her early life. Like Christian and their mother, she loved gardening, and especially flowers.

But there still remained a huge gap between the child Catherine, who I saw in the photographs at Villa les Rhumbs, and the hero Catherine, this woman who, against all odds, left Ravensbrück with her life in 1945.

So Many Forgotten Women

Justine Picardie, former editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar, UK, published a non-fiction book titled Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture about eighteen months after The Paris Secret was published, and for that whole time, I was avidly looking forward to reading it, eager to find out more about Catherine’s life. Picardie had been given access to the House of Dior archives and I imagined this would mean she’d find new information about Catherine that I hadn’t been able to uncover.

But Catherine really was a very private woman and apparently left very little trace of herself behind. Picardie’s book is a wonderful read and I can thoroughly recommend it, but there was no new information about Catherine.

This lack of records is a familiar story to anyone researching women in wartime, especially in France. It’s partly because everyone believed that war was men’s business, not women’s, so nobody believed the women’s stories about their Resistance work and capture. There was also a widespread belief that women who’d been in Nazi prison camps had been sexually assaulted, and no woman wanted anyone to think that about them at the time, so the women, because of self-preservation and undeserved shame, learned to keep their stories to themselves.

It breaks my heart that these brave women felt it was better to stay silent when they should have been so proud of all they had achieved.

Catherine’s story does end happily. After she returned from Ravensbrück, she married Hervé des Charbonneries, who’d also survived the war. And she was able to do something she loved for the rest of her life—she became the first female accredited to sell flowers at Les Halles marketplace in Paris. So she passed the rest of her years surrounded by flowers, which I think is a fittingly beautiful act three of her narrative.

Turning Scant Fact Into Fiction

But what it all meant for me, in writing Catherine into The Paris Secret as a character, was that I had to use a lot of imagination. Every time I wrote something about her, I tried to relate it back to the facts—she loved flowers, those who knew her adored her, she loved passionately but had a serious side to her, she was unselfish and so very strong to survive such deprivation for so long.

You can build a character out of that. You can build one whose thoughts and dialogue might be fictional in the words, but whose heart is as true as possible to what is known. I’m proud of how I wrote her into the story. I hope she would forgive me for the liberties I took. And I hope she’d be happy to know how strongly her story has resonated with people. She’s the one character I still get messages about, four years after the publication of my novel, from readers who were inspired by her courage and who are glad they’ve been able to know her, even if only a little.

This post is amazing, as are you. I discovered your books this year by purchasing The Disappearance Of Astrid Bricard. That story was so beautifully written, that I purchased the rest of your books. I am slowly making my way through; savoring each and every one. I am currently reading The Paris Secret. I am familiar with Catherine Dior’s story. I read Justine Picardie’s book and could not believe this was not widely known information. I have so much respect and admiration for her. She was one of the many true unsung heroes of that era. Through your tireless research and writing, you have given these women a voice again. I saw you once on Friends and Fiction when you were interviewed for the Alix St. Pierre novel. I was so intrigued, but like everything, life took over, and my retention is a bit like a Gnat, so poof, it was gone! When I saw the Bricard novel, I remembered that interview with F&F, and bought it on a whim. Boy, am I glad I discovered you. Thank you for hours and hours (and some sleepless nights) of reading pleasure. You are truly a master storyteller. I am new to Substack and promise I will not leave such long winded comments. I am just so thrilled that I have an opportunity to let you know how much I love your work, and to thank you for writing, and sharing so much of yourself with your readers. The joy and passion you have for what you do shows up in every word you write, and every story you weave. My sincere gratitude.