Courtesan and Muse, Or A Greater Designer Than Coco Chanel?

How a clue in the form of a flower led me to archives across the world that proved, without question, that yet another woman from history has been robbed of so much.

You might not be interested in fashion or fashion muses. But don’t let that put you off today’s post. This is the story of a research journey that led me around the world, a story of paying attention to the smallest clues, of finding a trail of evidence that’s somehow been ignored by almost every person who’s ever written Christian Dior’s so-called muse Mizza Bricard into a book or an article. Or perhaps the evidence wasn’t ignored – perhaps those writers didn’t bother to look for it. After all, the story of the male creative and his female muse is so well-known that it seems to have been accepted as truth in this case – and thus another female artist has had her genius stolen from her and given to the man whose name hangs on the awning outside the shop.

If you’ve seen me speak at an event on my recent book tour, this post is an expanded version, with lots more detail and images, of what I said at those events. And if you’ve read this article I wrote about Mizza, once again, this post is a much deeper dive into the tragedy of what history has done to Mizza Bricard. Also, some email systems like Gmail don’t like long posts so, if this gets cut off in your inbox, just click on the headline to be taken to Substack to read the full post.

The Knicker-less Whore … Apparently

Let’s start with some quotes from non-fiction books about Christian Dior that include a few paragraphs about Mizza Bricard to titillate the reader. From Marie-France Pochna’s oft-quoted 2008 biography of Dior:

“She never wore briefs and was only ever found in one of three places – at home, at the Ritz, or at Dior. It was said that she had once performed in a nude revue . . . she was feminine seduction incarnate.”

Now let’s turn to John Galliano and look at what he said about Mizza Bricard when he launched his Mizza-inspired collection for Dior:

“Have you gotten to the bit where Mr Dior says she never wore any knickers? She was the last of the demi-horizontale. She was fabulous!”

And onto an earlier book about Dior, one written before the deluge that have been published over the past five years or so:

“Mizza had once been a demimondaine – that is, an expensive prostitute . . . She was his muse.” Nigel Cawthorne, The New Look: The Dior Revolution

I could list dozens more similar quotes. Needless to say, all these writers go on to declare, unequivocally, that Mizza was Christian Dior’s muse. I want to reiterate that theses quotes come from non-fiction sources, so they’re meant to be true. Based on that, you’d be forgiven for thinking Mizza was a panty-less whore who existed only to stimulate Monsieur Dior to design beautiful dresses. That’s certainly what I believed when I began researching her a few years ago. What made me change my mind?

The Lily-of-the Valley Clue

When I started writing THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ASTRID BRICARD, I didn’t really intend to write a raging, alternative portrayal of Mizza. I wanted to look into the female muse/male creator story and pull it apart a bit. But then I stumbled across this line in an article written by Lourdes Font, who’s a professor in the Fashion and Textiles department at New York’s renowned FIT. She’s describing how Dior met Mizza, or Mitzah as it’s often anglicised:

“At Molyneux’s couture house, located in the rue Royale steps away from Dior’s apartment, he probably first made the acquaintance of Mitzah Bricard … She decorated the couturier’s [Molyneux’s] spring 1938 collection with one of his favorite flowers—the lily of the valley—placing “knots of them on every other dress” and on the simple hats …”

A seemingly unimportant piece of information, except that lily-of-the valley is one of the House of Dior’s “codes” – motifs that appear in most collections every year. Everyone says Dior began using it in his designs because he grew up surrounded by flowers in the garden of his family home in Granville. But here’s a renowned fashion professor saying that Mizza Bricard was using lily-of-the-valley back in 1938 at Molyneux, nine years before the House of Dior even existed.

Coincidence?

I didn’t think so. Add to that the fact that most of the non-fiction books and articles I’ve referred to above never even mention that Mizza worked at Molyneux prior to Dior and I knew I had to find out more. What was Mizza doing at Molyneux, for instance? Was she his muse too? Or something more?

The first thing I did was look at photographs of the hats at Molyneux’s spring 1938 collection. As you can see in the picture below, they’re adorned with lilies-of-the-valley. So it seemed that the professor’s assertion was at least partly true. And then I began wondering — did lily-of-the-valley become a House of Dior code because Christian grew up surrounded by flowers or because Mizza Bricard introduced it to him as a design idea? Was Mizza’s role at Dior bigger than we’d been lead to believe?

To Know Someone, You Need to Know Their Names

Thus began a research journey that took me to archives all across the world, into obscure corners of the Internet, and on a thrilling quest to prove that Mizza Bricard was so much more than what history had allowed her to be.

My first port of call was the Paris archives. If you want to find out about someone, you need to know the names they used in their lifetime. A couple of books and articles conjectured that Mizza’s real name was Germaine Louise Neustadt and that she was born in Paris in 1900. So I found her birth certificate, which you can see below. (I’ve cut out and enlarged the most important section).

The great thing about French birth certificates from that era is that every time a person has a civil event in their life, it’s recorded on the birth certificate. So if you marry or divorce, it’s all hand-written on to your original birth certificate.

As you can see in the image above, there’s a record of Mizza’s 1923 marriage to a Romanian man named Alexandra Bianu, which gave her the surname Biano. There’s also a record of a 1942 marriage to Hubert Henri Bricard, which gave her the Bricard surname. The other thing I knew from researching French women in the past is that they didn’t always use their first name. So I’d need to research Madame Biano and Madame Bricard as well as Mizza Bricard and Germaine Biano.

A New York Adventure

The next place I headed was ancestry.com. Lots of people use this for family tree research, but it’s also a historical novelist’s friend. Because, once again, it contains the records of people’s lives. Census records will give you the address where a person lived; shipping records will tell you where they travelled.

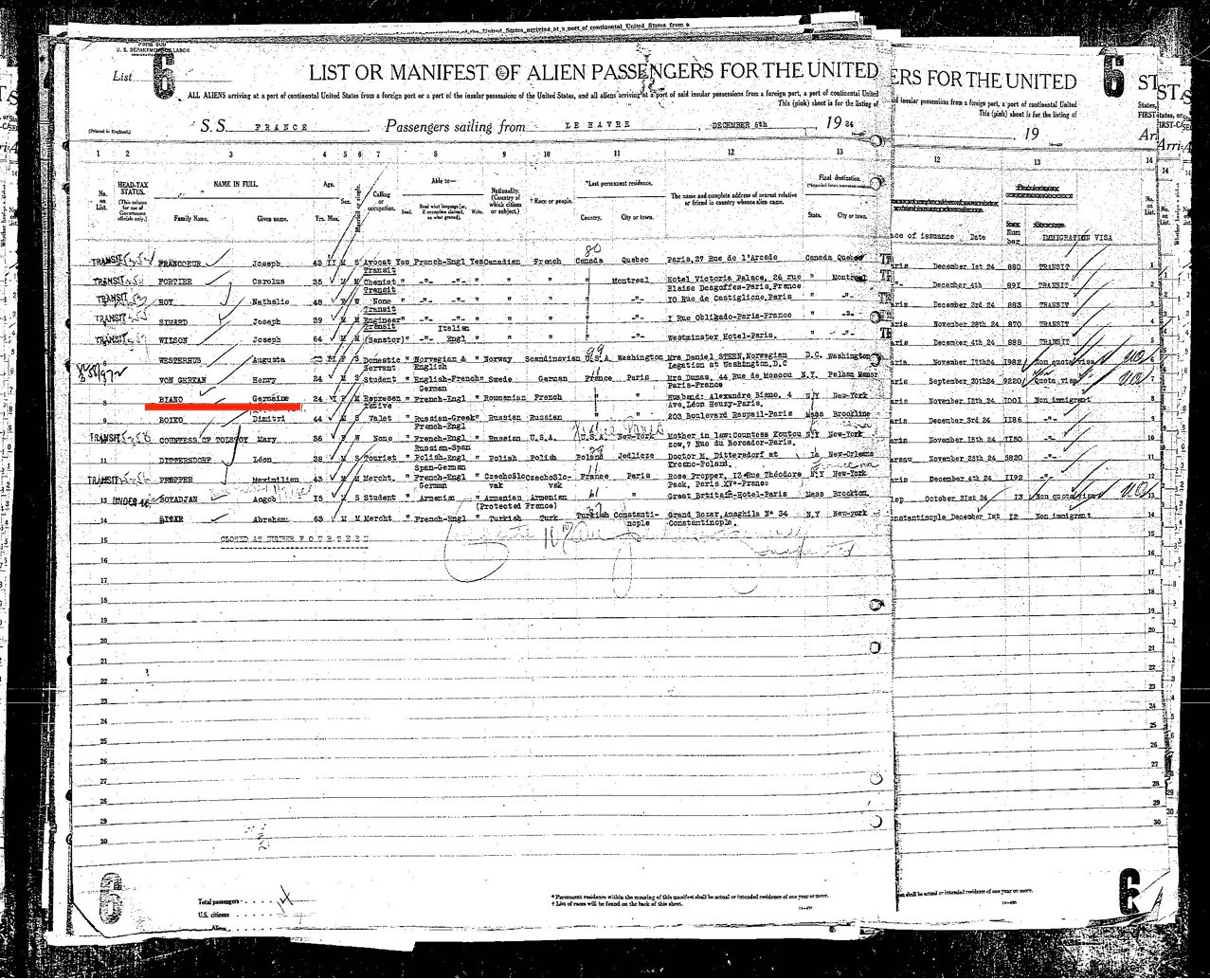

The first thing I found that made me sit up and pay attention was a shipping record from 1924. It showed that Mizza (or Germaine Biano) had, at just 24 years of age, travelled from Paris to New York. Back in 1924, most 24 year old women rarely left the village they were born in, let alone travelled across the world to another country. So what was she doing in New York?

Luckily, on page two, the shipping manifests also record the address of the place the traveller plans to spend most of their time. Mizza stated that she would be spending her time at the Harry Angelo Company on Fifth Avenue in New York City. So the next thing I did was to investigate exactly what the Harry Angelo Company was.

In the 1920s, French couturiers hadn’t yet set up their boutiques in Manhattan. Instead, they’d send their most trusted representative from Paris to New York once or twice a year to show the large garment manufacturers their designs. These garment manufacturers in New York would then purchase the right to make those designs for their American customers. Harry Angelo was one of those garment manufacturers.

It seems to me that the only possible explanation for why Mizza was travelling as a 24-year-old woman from Paris to New York to spend time at the Harry Angelo company was because she was the trusted representative of the French couturier, entrusted with showing the designs to Harry Angelo. That’s a pretty big responsibility for a 24-year-old woman. You don’t send the knicker-less demimondaine to do something like that, do you? You send someone who’s intelligent, who knows the designs well, who’s persuasive enough to be able to convince Harry Angelo to purchase those designs, a woman who is, in fact, nothing like the description of Mizza that’s been recorded in all those quotes I started with.

Of course this led me down another research rabbit hole. Which couturier was Mizza working for in the 1920s? How did she get from there to Molyneux in the 1930s? What exactly was her role in these couture houses?

European Spy, Cocotte, Or Just an Excellent Designer?

To find out the answers to those questions, I spent a lot more time inputting various combinations of Mizza’s names into different newspaper and magazine databases. The Vogue database. The newspapers.com database. And what I found was that Mizza began working for Paris couturier Doucet sometime in the early 1920s. From there, she moved to a Doucet-owned brand named Mirande where, according to a 1930 Vogue article (extract below), she designed “a great many models”. (Remember that “model” is the word for a design, whereas “mannequin” is the word for the woman who shows or parades the design in this era.)

But the key word here is designs. No mention of muse-dom. But someone who did the creative work.

In around 1933, Mizza left Mirande and went to Molyneux. Pierre Balmain, who began his career as an assistant designer at Molyneux, confirms this in his autobiography My Years and Seasons. He refers to Mizza as Madame B, and he seems equal parts fascinated and frightened of her, taking pains to describe the diamond star brooches she wore (stars are another House of Dior code!) and the scarf she always wore tied around her wrist to cover a scar that he conjectured was from vitriol burns.

This seems to be from where another story about Mizza grew – that one of her lovers’ wives threw acid on Mizza in a jealous rage. But let’s look at another tale of Mizza’s supposed retinue of lovers. Non-fiction writers always claim that her magnificent jewellery collection was furnished by said lovers. But on Mizza’s birth certificate, it says that the witness at her 1942 wedding was Jeanne Toussaint. Jeanne was Cartier’s jewellery designer. The person you choose to be your witness at your wedding is always a good friend. I found much more evidence to suggest that Mizza’s jewels were provided by her good friend and Cartier designer Jeanne (and perhaps from a White Russian prince she fell in love with in around 1917-1818) than that they were payoffs from lovers for services rendered. But of course the latter makes a much better headline, doesn’t it?!

Balmain also makes the throwaway claim that he could see Mizza “playing the role of a central European spy, or as one of the cocottes who revolutionised Maxim’s in 1900.” Unfortunately, it seems later writers took the second part of this offhand and fantastical remark and turned it into solid fact. But it’s interesting to look at Balmain’s motivations here. He admits to being envious of Mizza’s ability to speak fluent English to the Briton Molyneux and his two English deputies (Mizza was a polyglot who spoke at least four languages), envy at how she “electrified the atmosphere of the studio” and was also jealous of the fact that Molyneux generally picked many more of Mizza’s designs to be a part of each collection than he chose of Balmain’s designs.

Yes, that’s right – Mizza was designing for Molyneux. It was common practice in those days for the man whose name hung on the awning outside the boutique to employ assistant designers, who’d create designs that the couturier would then use in his collection. The assistant designers were never named, hardly acknowledged, but were always an integral part of each collection, as Mizza was at Molyneux.

So far, we’ve gathered evidence that Mizza was a fashion designer, with a definite je ne sais quoi when it came to enlivening the couture houses she worked at. No evidence that she couldn’t keep her panties on. What about after Molyneux left France when the Germans moved in?

One Of Balenciaga’s Closest Friends

Mizza worked at Balenciaga during the war. It’s unclear how long she was there for, and it’s also unclear what else she did between 1940 and 1944, although I have a few theories based on the number of résistant friends she had. What is clear is that she was one of Balenciaga’s very good friends. In her letters to fashion photographer Cecil Beaton and Princess Marthe Bibesco, which I discovered in two different archives, one in Cambridge in the UK and the other in Austin, Texas, she talks about spending much time in Balenciaga’s home in Spain. She vacationed with the great couturier.

In 1968, Paris Match photographed Balenciaga at his home in what is one of the very last shoots before he died. He chose four friends to be in that photo shoot at his home. One of those friends was Mizza Bricard.

Balenciaga is arguably one of the greatest couturiers of all time. It seems unlikely that he’d choose a knicker-less whore to share his final photo shoot for Paris Match. Isn’t it much more likely that he’d choose his most intimate friends, people whose minds he admired, and whose talents he also admired? (Please click here to see that photo shoot. It’s under copyright, so I can’t include any images here)

How Dare They?

Let’s take a look at those letters to Cecil Beaton that I mentioned above. Beaton is one of the most renowned fashion photographers of the 1930s-1950s. He had a long correspondence with Mizza and kept all of her letters. With those letters, Cecil also kept what he called a pen portrait of Mizza. He used to write descriptions of famous and interesting people and he published some of these in a book called The Glass of Fashion.

As I read through Cecil’s portrait of Mizza, I once again found a very different woman. I could quote many paragraphs as evidence of the grave injustice done to Mizza, but I’ll settle for this:

There are in the world of fashion those whose names have become almost household words merely through the good offices of their Personal Relations Officer. There are others who remain unsung, yet who are held in the highest respect by the brightest talents: Mizza Bricard is such a one . . . The greatest dressmakers know her worth … the great Balenciaga himself, as well as everyone in Paris who knows fashion, concedes that there are few women who are as knowledgeable on the subject as she.

And let’s back that assertion up with a statement made by Lady Jane Abdy in the obituary she wrote for Mizza, which was published in Harper’s and Queen in 1978:

In her modesty she submerged herself in the shadows of these great names, and never sought any personal recognition, though many considered her to be a greater designer than Coco Chanel.

A greater designer than Coco Chanel? Which means Mizza was a legendary, brilliant, incomparable designer. You can see why I was raging when I wrote THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ASTRID BRICARD. How dare the people who wrote history steal so much from her?

The Legendary Mizza

The last piece of evidence I’m going to present in my case that Mizza was a couturier in her own right, although she didn’t own a boutique or a fashion brand, is an article that was published in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper in 1950. The article is headed Dior’s Assistant: A Woman of Chic. You can see it in the photograph below.

Amongst other things, it says:

On the opening day of a new collection at the Maison Christian Dior, you will find, seated at the back of the main salon, a charming, ultra-smart, brown-haired woman in her early forties, whose keen green eyes are focused on every detail of the passing models … She is, in fact, a most important person on the Dior staff, second only to the great man himself, for she is Madame Germaine Biano-Bricard, first assistant designer to Christian Dior. She works with him in the creation of every model …” (emphasis mine)

So there it is, in black and white. Mizza was not just a muse. Somehow, Mizza has been demoted from her true role as Dior’s First Assistant Designer to an expensive prostitute.

A Gown With the Name Christian Dior Stamped in the Back

It’s interesting how, once you know the actual facts, you can look back over everything else that’s been written and re-see it in a new light. Let’s return to that quote from John Galliano that I presented at the start.

When he says, “have you read the bit where Mr Dior says she never wore any knickers?’ Galliano is referring to Dior’s memoirs. Dior published two; I have copies of both. Once I had this new version of Mizza my head, I realised I couldn’t recall ever seeing in one of Dior’s memoirs any paragraph that referred to Mizza not wearing any knickers. So I went back through both books to see if there was any mention of Mizza undressing herself or being unclothed in any way. This is the paragraph I found:

Madame Bricard comes in dressed in her work smock, jewellery, hat, and a little veil. She looks over the dress I am working on. She likes it or doesn’t. She undresses, puts it on herself, twists the sleeves, puts the front at the back, drapes the skirt into a pouf and opens the neckline. The effect is divine. A touch of fur trim and I have another dress.

What is this paragraph actually describing? It’s describing the process of Mizza Bricard designing a Dior gown. It’s describing her taking apart something that Christian Dior designed and then making it better. Making it new. Making it something that Dior would then show in his latest collection with the name Christian Dior stamped in the back of it.

Doesn’t it Make You Mad?

There should have been two names hanging over the awning outside that first Dior store. The brand should have been called, Christian Dior and Mizza Bricard. In every book and article written about Dior since he became one of the most famous couturiers in the world, there should at least be a chapter on the First Assistant Designer Mizza Bricard, who contributed so much to Dior’s success and to the couture house’s enduring success. But there isn’t. Doesn’t it make you mad?

As I said in the Author’s Note at the end of THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ASTRID BRICARD:

I don’t think anyone has to look too far to think of a woman who’s been remoulded by the media, by gossip, and by spite into something less than she actually was. It’s been happening for centuries, and it happens still. I hope historical novelists in one hundred years time aren’t still writing notes like this.

But commonsense and history tells me they probably will be.

That was an interesting piece of research, sad on a couple of levels. First, that she was so callously dismissed by contemporary critics. Second, that it was so easy (relatively) to find the truth. I'd like to think things are better now, and in many ways they are, but it is still all too easy to find those who will dismiss the accomplishments of women solely because they are women.

I'm speechless, but I guess I'm still able to write. How many times do other women have to unearth the real story behind these women who have been nearly erased from the past. Thank you SO much for this insightful and detailed report.